Table of Contents

This post was originally published on CodeFX.org. Because Java 9 draws ever closer we syndicate it here so you can get your hands dirty building a sample application on the Java Platform Module System (JPMS). The article was originally written in December 2015 and updated to the current state of affairs in February 2017.

In this post we’ll take an existing demo application and modularize it with Java 9. If you want to follow along, head over to GitHub, where all of the code can be found. The setup instructions are important to get the scripts running with Java 9. For brevity, I removed the prefix org.codefx.demo from all package, module, and folder names in this article.

The Application Before Jigsaw

Even though I do my best to ignore the whole Christmas kerfuffle, it seemed prudent to have the demo uphold the spirit of the season. So it models an advent calendar:

- There is a calendar, which has 24 calendar sheets.

- Each sheet knows its day of the month and contains a surprise.

- The death march towards Christmas is symbolized by printing the sheets (and thus the surprises) to the console.

Of course the calendar needs to be created first. It can do that by itself but it needs a way to create surprises. To this end it gets handed a list of surprise factories. This is what the main method looks like:

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<SurpriseFactory> surpriseFactories = Arrays.asList(

new ChocolateFactory(),

new QuoteFactory()

);

Calendar calendar =

Calendar.createWithSurprises(surpriseFactories);

System.out.println(calendar.asText());

}

The initial state of the project is by no means the best of what is possible before Jigsaw. Quite the contrary, it is a simplistic starting point. It consists of a single module (in the abstract sense, not the Jigsaw interpretation) that contains all required types:

- “Surprise API” – Surprise and

SurpriseFactory(both are interfaces) - “Calendar API” –

CalendarandCalendarSheetto create the calendar - Surprises – a couple of

SurpriseandSurpriseFactoryimplementations - Main – to wire up and run the whole thing.

Compiling and running is straight forward (commands for Java 8):

# compile

javac -d classes/advent ${source files}

# package

jar -cfm jars/advent.jar ${manifest and compiled class files}

# run

java -jar jars/advent.jar

Entering Jigsaw Land

The next step is small but important. It changes nothing about the code or its organization but moves it into a Jigsaw module.

Modules

So what’s a module? To quote the highly recommended State of the Module System:

A module is a named, self-describing collection of code and data. Its code is organized as a set of packages containing types, i.e., Java classes and interfaces; its data includes resources and other kinds of static information.

To control how its code refers to types in other modules, a module declares which other modules it requires in order to be compiled and run. To control how code in other modules refers to types in its packages, a module declares which of those packages it exports.

(The last paragraph is actually from an old version of the document but I like how it summarizes dependencies and exports.)

So compared to a JAR a module has a name that is recognized by the JVM, declares which other modules it depends on and defines which packages are part of its public API.

Name

A module’s name can be arbitrary. But to ensure uniqueness it is recommended to stick with the inverse-URL naming schema of packages. So while this is not necessary it will often mean that the module name is a prefix of the packages it contains.

Dependencies

A module lists the other modules it depends on to compile and run. This is true for application and library modules but also for modules in the JDK itself, which was split up into about 100 of them (have a look at them with java --list-modules).

Again from the design overview:

When one module depends directly upon another in the module graph then code in the first module will be able to refer to types in the second module. We therefore say that the first module reads the second or, equivalently, that the second module is readable by the first.

[…]

The module system ensures that every dependence is fulfilled by precisely one other module, that the module graph is acyclic, that every module reads at most one module defining a given package, and that modules defining identically-named packages do not interfere with each other.

When any of the properties is violated, the module system refuses to compile or launch the code. This is an immense improvement over the brittle classpath, where e.g. missing JARs would only be discovered at runtime, crashing the application.

It is also worth to point out that a module is only able to access another’s types if it directly depends on it. So if A depends on B, which depends on C, then A is unable to access C unless it requires it explicitly.

Exports

A module lists the packages it exports. Only public types in these packages are accessible from outside the module.

This means that public is no longer really public. A public type in a non-exported package is as inaccessible to the outside world as a non-public type in an exported package. Which is even more inaccessible than package-private types are before Java 9 because the module system does not even allow reflective access to them. As Jigsaw is currently implemented command line flags are the only way around this.

Implementation

To be able to create a module, the project needs a module-info.java in its root source directory:

module advent {

// no imports or exports

}

Wait, didn’t I say that we have to declare dependencies on JDK modules as well? So why didn’t we mention anything here? All Java code requires Object and that class, as well as the few others the demo uses, are part of the module java.base. So literally every Java module depends on java.base, which led the Jigsaw team to the decision to automatically require it. So we do not have to mention it explicitly.

The biggest change is the script to compile and run (commands for Java 9):

# compile (include module-info.java)

javac -d classes/advent ${source files}

# package (add module-info.class and specify main class)

jar --create \

--file=mods/advent.jar \

--main-class=advent.Main \

${compiled class files}

# run (specify a module path and simply name to module to run)

java --module-path mods --module advent

We can see that compilation is almost the same – we only need to include the new module-info.java in the list of classes.

The jar command will create a so-called modular JAR, i.e. a JAR that contains a module. Unlike before we need no manifest anymore but can specify the main class directly. Note how the JAR is created in the directory mods.

Utterly different is the way the application is started. The idea is to tell Java where to find the application modules (with --module-path mods, this is called the module path) and which module we would like to launch (with --module advent).

Splitting Into Modules

Now it’s time to really get to know Jigsaw and split that monolith up into separate modules.

Made-up Rationale

The “surprise API”, i.e. Surprise and SurpriseFactory, is a great success and we want to separate it from the monolith.

The factories that create the surprises turn out to be very dynamic. A lot of work is being done here, they change frequently and which factories are used differs from release to release. So we want to isolate them.

At the same time we plan to create a large Christmas application of which the calendar is only one part. So we’d like to have a separate module for that as well.

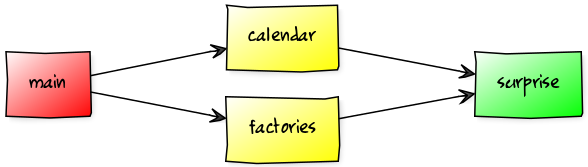

We end up with these modules:

- surprise –

SurpriseandSurpriseFactory - calendar – the calendar, which uses the surprise API

- factories – the

SurpriseFactoryimplementations - main – the original application, now hollowed out to the class

Main

Looking at their dependencies we see that surprise depends on no other module. Both calendar and factories make use of its types so they must depend on it. Finally, main uses the factories to create the calendar so it depends on both.

Implementation

The first step is to reorganize the source code. We’ll stick with the directory structure as proposed by the official quick start guide and have all of our modules in their own folders below src:

src

- advent.calendar: the "calendar" module

- org ...

module-info.java

- advent.factories: the "factories" module

- org ...

module-info.java

- advent.surprise: the "surprise" module

- org ...

module-info.java

- advent: the "main" module

- org ...

module-info.java

.gitignore

compileAndRun.sh

LICENSE

README

To keep this readable I truncated the folders below org. What’s missing are the packages and eventually the source files for each module. See it on GitHub in its full glory.

Let’s now see what those module infos have to contain and how we can compile and run the application.

surprise

There are no required clauses as surprise has no dependencies. (Except for java.base, which is always implicitly required.) It exports the package advent.surprise because that contains the two classes Surprise and SurpriseFactory.

So the module-info.java looks as follows:

module advent.surprise {

// requires no other modules

// publicly accessible packages

exports advent.surprise;

}

Compiling and packaging is very similar to the previous section. It is in fact even easier because surprise contains no main class:

# compile

javac -d classes/advent.surprise ${source files}

# package

jar --create --file=mods/advent.surprise.jar ${compiled class files}

calendar

The calendar uses types from the surprise API so the module must depend on surprise. Adding requires advent.surprise to the module achieves this.

The module’s API consists of the class Calendar. For it to be publicly accessible the containing package advent.calendar must be exported. Note that CalendarSheet, private to the same package, will not be visible outside the module.

But there is an additional twist: We just made Calendar.createWithSurprises(List<SurpriseFactory>) publicly available, which exposes types from the surprise module. So unless modules reading calendar also require surprise, Jigsaw will prevent them from accessing these types, which would lead to compile and runtime errors.

Marking the requires clause as transitive fixes this. With it any module that depends on calendar also reads surprise. This is called implied readability.

The final module-info looks as follows:

module advent.calendar {

// required modules

requires transitive advent.surprise;

// publicly accessible packages

exports advent.calendar;

}

Compilation is almost like before but the dependency on surprise must of course be reflected here. For that it suffices to point the compiler to the directory mods as it contains the required module:

# compile (point to folder with required modules)

javac --module-path mods \

-d classes/advent.calendar \

${source files}

# package

jar --create \

--file=mods/advent.calendar.jar \

${compiled class files}

factories

The factories implement SurpriseFactory so this module must depend on surprise. And since they return instances of Surprise from published methods the same line of thought as above leads to a requires transitive clause.

The factories can be found in the package advent.factories so that must be exported. Note that the public class AbstractSurpriseFactory, which is found in another package, is not accessible outside this module.

So we get:

module advent.factories {

// required modules

requires public advent.surprise;

// publicly accessible packages

exports advent.factories;

}

Compilation and packaging is analog to calendar.

main

Our application requires the two modules calendar and factories to compile and run. It still has no API to export.

module advent {

// required modules

requires advent.calendar;

requires advent.factories;

// no exports

}

Compiling and packaging is like with last section’s single module except that the compiler needs to know where to look for the required modules:

#compile

javac --module-path mods \

-d classes/advent \

${source files}

# package

jar --create \

--file=mods/advent.jar \

--main-class=advent.Main \

${compiled class files}

With all the modules in mods , we can run the calendar.

# run

java --module-path mods --module advent

Services

Jigsaw enables loose coupling by implementing the service locator pattern, where the module system itself acts as the locator. Let’s see how that goes.

Made-up Rationale

Somebody recently read a blog post about how cool loose coupling is. Then she looked at our code from above and complained about the tight relationship between main and factories. Why would main even know factories?

Because…

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<SurpriseFactory> surpriseFactories = Arrays.asList(

new ChocolateFactory(),

new QuoteFactory()

);

Calendar calendar =

Calendar.createWithSurprises(surpriseFactories);

System.out.println(calendar.asText());

}

Really? Just to instantiate some implementations of a perfectly fine abstraction (the SurpriseFactory)?

And we know she’s right. Having someone else provide us with the implementations would remove the direct dependency. Even better, if said middleman would be able to find all implementations on the module path, the calendar’s surprises could easily be configured by adding or removing modules before launching.

this is exactly what services are there for! We can have a module specify that it provides implementations of an interface. Another module can express that it uses said interface and find all implementations with the ServiceLocator.

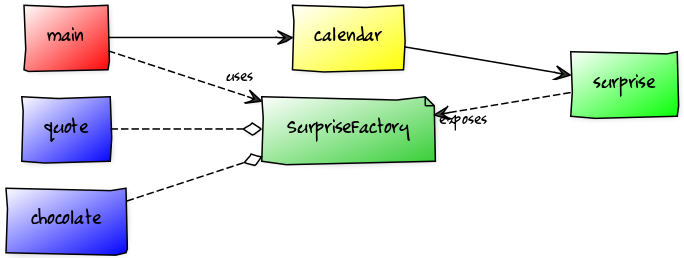

We use this opportunity to split factories into chocolate and quote and end up with these modules and dependencies:

- surprise –

SurpriseandSurpriseFactory - calendar – the calendar, which uses the surprise API

- chocolate – the

ChocolateFactoryas a service - quote – the

QuoteFactoryas a service - main – the application; no longer requires individual factories

Implementation

The first step is to reorganize the source code. The only change from before is that src/advent.factories is replaced by src/advent.factory.chocolate and src/advent.factory.quote.

Lets look at the individual modules.

surprise and calendar

Both are unchanged.

chocolate and quote

Both modules are identical except for some names. Let’s look at chocolate because it’s more yummy.

As before with factories the module requires transitive the surprise module.

More interesting are its exports. It provides an implementation of SurpriseFactory, namely ChocolateFactory, which is specified as follows:

provides advent.surprise.SurpriseFactory

with advent.factory.chocolate.ChocolateFactory;

Since this class is the entirety of its public API it does not need to export anything else. Hence no other export clause is necessary.

We end up with:

module advent.factory.chocolate {

// list the required modules

requires public advent.surprise;

// specify which class provides which service

provides advent.surprise.SurpriseFactory

with advent.factory.chocolate.ChocolateFactory;

}

Compilation and packaging is straight forward:

javac --module-path mods \

-d classes/advent.factory.chocolate \

${source files}

jar --create \

--file mods/advent.factory.chocolate.jar \

${compiled class files}

main

The most interesting part about main is how it uses the ServiceLocator to find implementation of SurpriseFactory. From its main method:

List surpriseFactories = new ArrayList<>();

ServiceLoader.load(SurpriseFactory.class)

.forEach(surpriseFactories::add);

Our application now only requires calendar but must specify that it uses SurpriseFactory. It has no API to export.

module advent {

// list the required modules

requires advent.calendar;

// list the used services

uses advent.surprise.SurpriseFactory;

// exports no functionality

}

Compilation and execution are like before.

And we can indeed change the surprises the calendar will eventually contain by simply removing one of the factory modules from the module path. Neat!

Summary

So that’s it. We have seen how to move a monolithic application into a single module and how we can split it up into several. We even used a service locator to decouple our application from concrete implementations of services. All of this is on GitHub so check it out to see more code!

But there is lots more to talk about! Jigsaw brings a couple of incompatibilities but also the means to solve many of them. And we haven’t talked about how reflection interacts with the module system and how to migrate external dependencies.

If these topics interest you, watch this tag as I will surely write about them over the coming months.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Java Module System

What is the main difference between the classpath and the modulepath in Java 9?

The classpath and the modulepath are both mechanisms used in Java to locate classes and resources. However, they function differently. The classpath, which has been a part of Java since its inception, is a parameter that tells the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) where to find user-defined classes and packages. It can lead to issues like classpath hell due to its flat class loading mechanism. On the other hand, the modulepath was introduced in Java 9 as part of the Java Platform Module System (JPMS). It allows the JVM to find modules, which are larger units of organization than packages. The modulepath helps to avoid classpath hell by enforcing encapsulation and reliable configuration.

How does the Java Module System improve security?

The Java Module System enhances security by introducing strong encapsulation. This means that a module can specify which of its public types are accessible to other modules, and which are not. This prevents unauthorized access to internal classes and methods, thereby reducing the surface area for attacks.

What is a module descriptor in Java 9?

A module descriptor is a file named module-info.java that is placed in the root directory of a module’s source code. It defines the module’s name, the modules it requires, and the packages it exports. The module descriptor is essential for the Java compiler and runtime system to understand the module’s dependencies and the APIs it provides.

How does the Java Module System handle dependencies?

The Java Module System handles dependencies through the ‘requires’ keyword in the module descriptor. When a module requires another module, it means that it depends on that module to function correctly. The Java compiler and runtime system use this information to ensure that all necessary modules are present and to avoid loading unnecessary modules.

Can I still use JAR files with the Java Module System?

Yes, you can still use JAR files with the Java Module System. In fact, a modular JAR file is simply a JAR file that includes a module descriptor. This means you can easily modularize existing libraries by adding a module-info.java file to them.

What is the ‘exports’ keyword in a module descriptor?

The ‘exports’ keyword in a module descriptor is used to specify which packages in the module are accessible to other modules. This is part of the strong encapsulation provided by the Java Module System. If a package is not exported, it is not accessible outside the module, even if its classes and interfaces are public.

What is the ‘uses’ keyword in a module descriptor?

The ‘uses’ keyword in a module descriptor is used to specify a service that the module consumes. A service in this context is an implementation of an interface or abstract class that can be used by other modules. The ‘uses’ keyword allows a module to declare that it uses a particular service without knowing or caring about the implementing class.

What is the ‘provides’ keyword in a module descriptor?

The ‘provides’ keyword in a module descriptor is used to specify that the module provides an implementation of a service. This is the counterpart to the ‘uses’ keyword. A module that provides a service must include the ‘provides’ keyword in its module descriptor, along with the name of the service interface and the name of the implementing class.

How does the Java Module System affect performance?

The Java Module System can improve performance by reducing the runtime footprint and startup time of applications. This is because the module system allows the JVM to load only the necessary modules for an application, rather than loading all classes on the classpath. Furthermore, the module system enables advanced techniques like ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation and linking, which can significantly improve startup performance.

Can I mix modular and non-modular code in a Java application?

Yes, you can mix modular and non-modular code in a Java application. Non-modular code (code without a module descriptor) is treated as part of an unnamed module, which depends on all other modules. This allows for a gradual migration to the module system. However, it’s important to note that the unnamed module does not have access to non-exported packages in named modules, which can lead to issues if the non-modular code uses internal APIs of libraries.

Nicolai is a thirty year old boy, as the narrator would put it, who has found his passion in software development. He constantly reads, thinks, and writes about it, and codes for a living as well as for fun. Nicolai is the former editor of SitePoint's Java channel, writes The Java 9 Module System with Manning, blogs about software development on codefx.org, and is a long-tail contributor to several open source projects. You can hire him for all kinds of things.