A console is a software artifact for reading line-oriented textual input from the keyboard and writing line-oriented textual output to the screen. Consoles are often used to implement operating systemcommand-line interfaces, but are also handy in text-based adventure games and other contexts.

Although text-oriented consoles are not as popular as they once were because of the proliferation of graphical user interfaces, they can be useful to power users who are not intimidated by this style of interface. Also, consoles can open up a new class of web application such as the embedded browser shell.

This article begins a two-part series that presents a JavaScript-based console library for use with web applications that may benefit from this style of user interface. Part 1 introduces you to the library’s simple API along with a browser shell application that serves as a useful demonstration of this API. Part 2 shows you how the library is implemented so that you can modify it to meet additional requirements.

Explore the Console Library

The console library consists of a global object named Console with several properties. This arrangement minimizes pollution of the global namespace. Furthermore, it reflects my desire to avoid supporting multiple consoles, as I find it easier to implement a singleton console.

Console provides the following features:

- easy initialization based on number of desired rows and columns (the

<canvas>tag requires only anidattribute)

- canvas placed in tab order and gains keyboard focus immediately for browsers such as Firefox

- clear console capability

- green on black text with monospace font

- visible cursor that marks the current input position

- text echoing capability

- vertically scrollable when text flows past the lower-right character position

- simplified editing in terms of the backspace key

- automatically call a function when no input is available

- supports FireFox, Internet Explorer, Chrome, Opera, and Safari

Although Console encapsulates multiple accessible properties, I consider only four of them to be members of the “public” API. The other properties should not be accessed; they exist to support the following four properties and could change in a subsequent version of the library:

init(canvasName, numCols, numRows)initializes the console. The string passed tocanvasNamemust match the value of an existing<canvas>element’sidattribute. The integer passed tonumColsidentifies the desired number of columns (e.g., 80), and the integer passed tonumRowsidentifies the desired number of rows (e.g., 25). The console is cleared and the cursor position is set (0, 0). The resulting console displays green text on a black background. This function does not return a value.

clear()clears the console and sets the cursor position to (0, 0). This function does not return a value.

getLine(callback)returns a line of input and echoes this input to the console. It first checks if a line has been entered by noting whether a newline character (indicated by the user having pressed the key labeled Enter or Return) is present in the input. If so, the line is returned without the newline character. If a newline is not present, or if there is no input, this function returns null. When a function is passed tocallback, that function is called when nothing has been entered.

echo(msg)echoes the string passed tomsgto the console starting at the cursor position, which is updated. The console scrolls vertically when the message flows past the lower-right corner. This function recognizesb(backspace) andn(newline) special characters. Also, it does not return a value.

The getLine(callback) function does not block the current thread while waiting for the user to press Enter/Return. Instead, it returns immediately. It does so because JavaScript code runs on a single thread. (HTML5’s web workers are an exception, and are beyond the scope of this article.) Blocking this thread for longer than what the browser considers acceptable causes the browser to display a dialog box that reports an unresponsive script.

The console library is easy to use. After defining a <canvas> element, and after initializing and echoing any preliminary text to the console, repeatedly execute a function via JavaScript’ssetInterval() function. Each execution should invoke getLine(callback) (with an optional callback function) and then take appropriate action based on getLine()‘s return value. Listing 1 presents the HTML for a simple demonstration of this library.

<html>

<head>

<title>

Console Demo

</title>

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=Edge"/>

<script src="../Console/Console.js">

</script>

</head>

<body style="text-align: center">

<p>

<h2>

Console Demo

</h2>

<canvas id="mycanvas">

HTML5 canvas element not supported by this browser.

</canvas>

<p>

You might have to press the Tab key or click the canvas to give it keyboard focus.

</p>

<script>

Console.init("mycanvas", 64, 16);

Console.echo(">");

function tick()

{

var line = Console.getLine();

if (line != null)

{

if (line != "")

Console.echo(line+"n");

Console.echo(">");

}

}

setInterval("tick()", 50); // Invoke tick() every 50 milliseconds.

</script>

</body>

</html>

Listing 1: Echoing entered text on the console

Listing 1 describes ConsoleDemo.html. This listing is fairly straightfoward, except perhaps for the <meta> element. This element enforces a compatibility mode — use latest standards rendering mode — so that the console will work under Internet Explorer 9 (and probably higher versions of this browser). Otherwise, Explorer outputs an error message about the Canvas API’s getContext() function not being defined.

Listing 1 continues with a <script> element that includes the contents of a JavaScript source file named Console.js. This file defines the console library and is located in a Console directory that’s accessed relative to ConsoleDemo.html. The code file that’s attached to this article contains ConsoleDemo.html and Console.js in appropriate directories relative to each other, so you should be able to run ConsoleDemo without problems.

The body of this HTML file specifies a <canvas> element whose id attribute is assigned mycanvas. No other attribute is required because the console library takes care of them. The body also contains a <script> element that presents the console demonstration code.

The code first initializes the canvas to a 64-column-by-16-row drawing area — I chose these values because they were the dimensions of the text screen on my old TRS-80 Model III microcomputer. The code then echoes a > character to the console as the initial input line’s prompt.

At this point, a function named tick() is defined for repeated execution. This function will be executed every 50 milliseconds courtesy of the setInterval("tick()", 50) function call. Each invocation attempts to retrieve and echo back to the console a line of input.

tick() first invokes getLine() without passing a callback function because none is needed in this example. If this function returns null because nothing has been entered or the user is typing some input (and has not yet pressed Enter/Return), nothing further happens. Otherwise, if the returned line is not equal to the empty string (only Enter/Return was pressed), the entered text followed by a newline is echoed to the console. At this point, a > prompt is echoed to inform the user that another line of input is expected.

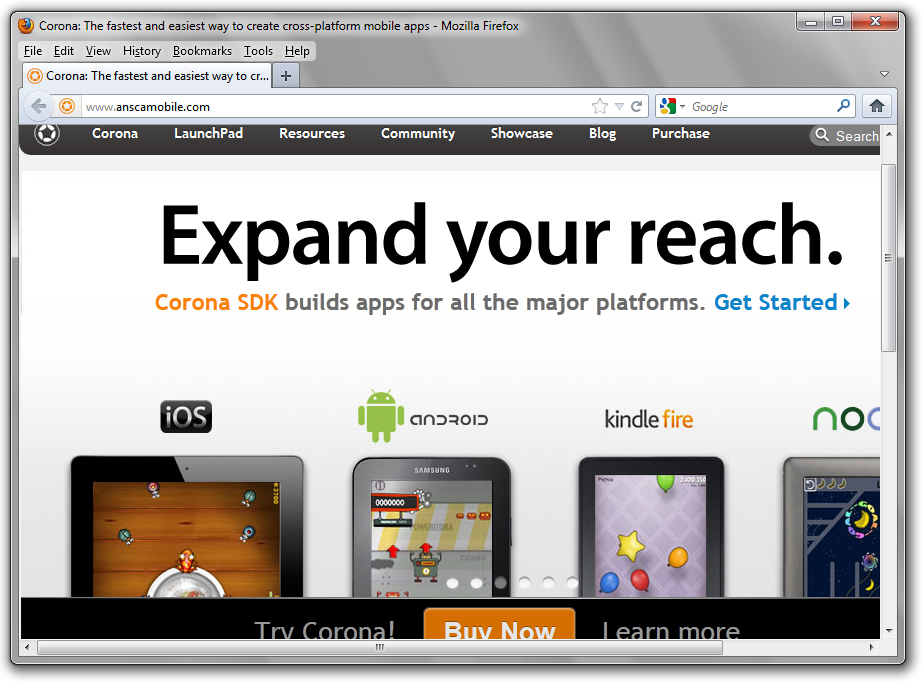

Figure 1 shows you the resulting console in the context of Firefox.

Figure 1: You don’t have to press Tab to start using the console on Firefox.

Encounter a Browser Shell

A shell provides an operating system’s user interface, and its primary purpose is to run programs. Modern operating systems feature graphical shells, but many also feature traditional command-line-oriented shells (e.g, Unix’s Korn and Bourne shells). A similar shell can be embedded within a web page via the console library, and this browser shell can be used to execute browser-oriented commands.I’ve created a browser shell application as a useful demonstration of the console library. Figure 2 reveals this application’s console in the context of the Internet Explorer 9 browser.

Figure 2: The browser shell currently supports four commands.

Figure 2 reveals an interesting anomaly: geolocation information is not immediately displayed. Instead, latitude and longitude data is often presented multiple lines later in the browser. You will learn the reason while exploring Listing 2.

<html>

<head>

<title>

Browser Shell

</title>

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=Edge"/>

<script src="../Console/Console.js">

</script>

</head>

<body style="text-align: center">

<p>

<h2>

Browser Shell

</h2>

<canvas id="mycanvas">

HTML5 canvas element not supported by this browser.

</canvas>

<p>

You might have to press the Tab key or click the canvas to give it keyboard focus.

</p>

<script>

Console.init("mycanvas", 64, 22);

Console.echo("Browser Shell 1.0nn");

Console.echo("Type 'help' (without the quotes) to obtain helpnn");

Console.echo(">");

var geo = "";

function callback()

{

if (geo == "")

return;

Console.echo(geo+"n");

Console.echo(">");

geo = "";

}

function tick()

{

var line = Console.getLine(callback);

if (line != null)

{

line = line.trim();

if (line == "browser")

Console.echo(navigator.userAgent+"nn"); else if (line == "cls") Console.clear(); else if (line == "geo") { Console.echo("querying location info...may take a few momentsnn"); function report_error(error) { geo = error.message; if (geo == "") // geo is "" on Safari geo = "unknown error"; } function report_geolocation_query(position) { geo = "Lat: "+position.coords.latitude+", Lon: "+position.coords.latitude; } navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition(report_geolocation_query, report_error); } else if (line == "help") { Console.echo("Available commands...n"); Console.echo("browser -- display current browser infon"); Console.echo("cls -- clear screenn"); Console.echo("geo -- obtain geolocation informationn"); Console.echo("help -- display this help textnn"); } else if (line != "") Console.echo("bad commandn"); Console.echo(">"); } } setInterval("tick()", 50); // Invoke tick() every 50 milliseconds. </script> </body> </html>

Listing 2: Interpreting and executing commands

Listing 2 presents BrowserShell.html. This listing has a similar layout to Listing 1 and should be fairly easy to follow. After initializing and echoing preliminary text to the console, the tick()function is repeatedly executed to get the next line of input, trim whitespace from both ends, check for one of four possible commands, and execute the command. If an invalid command is entered, bad command is echoed to the console. Regardless, the user is then prompted to enter the next command.

The geo command is the most complex to implement. It obtains geolocation information about the user via the Geolocation API, which is asynchronous to avoid blocking the JavaScript thread.navigator.geolocation. queries the user to grant permission to obtain geolocation information, proceeds to get that information when the user accepts, and then invokes one of two callback functions:

report_geolocation_query(is invoked (upon success) with aposition) Positionargument that stores the geolocation data via itscoordsmember, of Document Object Model typeCoordinates. This DOM interface includeslatitudeandlongitudefields of DOM typedouble.

report_error(error)is invoked (upon failure) with aPositionErrorargument that stores the reason for failure via itsmessagemember, of DOM typeDOMString, and itscodemember, of DOM typeunsigned short.

Each of these callbacks extracts information from its passed argument and builds a string that it assigns to the geo variable. During testing on Safari, I discovered that this browser wouldn’t let me obtain geolocation information. Furthermore, it assigned the empty string to message. To address this situation, I coded report_error(error) to assign "unknown error" to message. (I could have output a message based on error.code whose value was 2 — the position is unavailable. I leave making this change with you as an exercise.)

Listing 2 declares a callback() function that it passes as an argument to getLine(callback). This function is invoked each time getLine(callback) detects that there is no input. After verifying that something has been assigned to geo, callback() echoes this variable’s value followed by a > prompt to the console, and then assigns the empty string to this variable (to avoid having geo‘s value repeatedly output).

Why don’t I echo geo‘s value within report_geolocation_query( and report_error(error) (and then I wouldn’t need geo but could use a local variable) instead of going to the trouble of passing a callback function to getLine(callback)? If I did so, that navigation data could be output in the midst of entering a command, resulting in a mess. For example, while entering help I might end up with the following intermixed output:

>helLat: 49.88, Lon: 49.88 >p

Conclusion

Console is a useful tool for embedding a simple console into web pages. The previous browser shell application gives you an idea of what’s possible. You might want to extend this application with additional commands, such as a dir command for obtaining a directory listing of web storage. However, you first need to understand how this library works, and that is the subject of Part 2.

| Note |

|---|

| All files pertaining to this article are located in code.zip. |

Jeff Friesen

Jeff FriesenJeff Friesen is a freelance tutor and software developer with an emphasis on Java and mobile technologies. In addition to writing Java and Android books for Apress, Jeff has written numerous articles on Java and other technologies for SitePoint, InformIT, JavaWorld, java.net, and DevSource.